The international website ArtWay for art in Christian context has published (15.01.12): The Ecclesial Context. Exploring Sacred Space as Site for Contemporary Art Intervention. Paper read at Sensuous Knowledge 4, 7-9 November 2007, at Solstrand, Bergen.

The Ecclesial Context. Exploring Sacred Space as Site for Contemporary Art Intervention

by Grete Refsum

Introduction

This paper deals with the ecclesial challenge that is currently offered contemporary artists. Its point of departure is twofold: The Norwegian Evangelical Lutheran Church’s foundational document on its relationship to culture and the arts, from 2005: Kunsten a vaere kirke; om kirke, kunst og kultur,2 and the author’s art intervention in Oslo Cathedral, in 2005.

Kunsten a vaere kirke boldly addresses the split that arose between the arts and the Church during Modernism. But the arts and the Church have much in common; now is time to start anew and enter into a respectful dialogue. The text says:

Both [the arts and the Church] try to create a room for reflection about what it means to be human [ … ] whatever the point of reference, Christian or not, the task is to seek places for meeting in which we can collaborate in tracing the sketches to a meaning that has to be reconstructed again and again.3

From a secular point of view, theology is today recognized not only as a dogmatic restraint of thinking, but rather a constructive resource to reflect on the human condition.4 This attitude is met in the new document, saying:

The Church has to reconquer some of its lost tradition of being a force of renewal in the arts. It has to actively break with the timidity that has marked the relation between the Church and the arts for generations. Instead of taking a conservative, controlling and skeptical attitude to contemporary art, it has to become a collaborator to develop the expressions of art. If the Church is to have a true presence in today’s society and know and understand the human heart, it is important that it arranges so that contemporary voices can be heard.5

When Kunsten a vaere kirke was launched, the Evangelical Lutheran Cathedral in Oslo wished to be in front of the tide. The vicar invited contemporary artists, me being one of them, to propose ideas for interventions in the church room itself, not only the crypt gallery below the church room that is used for exhibitions, including contemporary art projects. The Cathedral is protected by law; the proposals, therefore, would be evaluated in relation both to the acceptance of the church authorities, the congregation and the bishop, and the regulations on the building.

Contrary to what may be anticipated, and the practices within the Orthodox Churches, Western Churches have no explicit mies on art, only normative statements that are negotiabie and open to interpretation. However, traditions and expectations to art in church contexts may be stronger than the current official advocacy of adopting a positive attitude to contemporary art. The question is how artists may cope with a situation th at is both open and restricted. Wh at do ecclesial patrons expect from artists, and where are their borders of tolerance? What can artists offer without abandoning their claim to autonomy? How can the two communicate their legitimate needs and restrictions? For practicing artists these questions may boil down to: What should the artist consider when doing ecclesial work?

The paper aims at contributing to shed light on the raised questions. It firstly defines terminology. Secondly, it treats general criteria (Western Christian) for producing art in church contexts today, suggesting a simple model that may help patrons and artists communicate. Thirdly, the theory is exemplified the author’s Pater Noster project carried out in Oslo Cathedral.

Terminology

There is currently no consistent vocabulary on art related to religion and church either in English, German, or the Scandinavian languages (Refsum 2000: 40). In order to understand the discourse on the arts and the Church, it may be worth while to take a c10ser look at the terrninology because it reveals certain attitudes that may have consequences for the artworks and their production.

When art is made for use in church buildings it is defined by adjectives like sacred, liturgical or ecclesial.6

Sacred Art

Sacred means that which belongs to the realm of the holy: worship, persons, and things marked out by consecration, that is, actions which set objects apart from profane use (Rahner and Vorgrimler 1983: 90). Broadly speaking, churches are dedicated for worship and thereby considered sacred spaces.7 Consequently, art placed in church rooms is of ten denoted sacred art. However, an object does not become sacred in itself by being situated in a sacred space. The late Norwegian Lutheran theologian Helge Frehn defines: “An object is sacred when its function, material, and form aim at serving the people of God in their common, liturgical life” (Frehn 1968: 82).8 Defined this way, sacred art becomes synonymous to liturgical art.

Liturgical art

The main activity and most important Christian ritual is the service, the mass. It consists of a set sequence of components: prayers, readings and actions that taken together are called liturgy, denoting the official worship of God.9 In consequence, liturgical art is defined by its function, which is to serve the liturgy, the specific needs of public worship and private devotion in church.

Ecclesial Art

The word church sterns from Greek Ekklesia, Latin ecclesia, which has a double meaning. Written with major E, Ecclesia, it denotes the living organism of people of faith in the world, and its administrative institution. Written with minor e, ecclesia, it simply refers to the buildings that houses the faithful. lt follows that ecclesial art is defined as art serving Ecclesia and most of ten is to be found in church rooms (Jungmann, 1955: 68). Personally, I prefer ecclesial art to sacred and liturgical art. This term is not bound to a pretension of being in itself sacred or linked to the liturgy; it is open to the service of Ecclesia in a broad sense th at I find compatible with the attitude in Kunsten a vaere kirke.10

Contemporary Art

Contemporary art of any kind may be taken into Christian or ecclesial contexts as art in a secular sense, regardless of its potential function as vocational, catechetical or decorative. We may say that art as such goes beyond these categories, maybe comprising them all. However, whatever the artist intends, when a work is taken into the ecclesial context, it somehow will be interpreted within in it. Instead of reacting negatively to it, this is a fact artists should be aware of and consider before engaging with ecclesial contexts.

General Criteria

Theologians and Church leaders have throughout history repeatedly attempted to set forth more or less universal guidelines for the arts of the Church.

Characteristics of Ecclesial Art

According to the US Professor of religion and humanities, musician and composer Frank Burch Brown, the most frequent criteria in modern times have been: simplicity, dignity, order, restraint, beauty, harmony, sincerity, and truthfulness (Brown 1995: 323-24). The Norwegian art historian Henrik von Achen has listed several points concerning art in ecclesial use.11 According to him, ecclesial art should primarily deserve to be called art; it should not merely be decorative, but a “talk about God” that would strengthen the function of the place it embellishes. Besides, the arts in a church should keep contact with tradition; be authentic, reflecting the dynamic element in Christian tradition; be pastoral and communicate faith. Artists working ecclesial spaces should be given the necessary freedom to create, but at the same time they have to be loyal to the task. The ecclesial patron keeps the authority regarding the content of the artwork, and should be a mediator between the faithful and the artist. Finally, von Achen advices that a congregation should be willing to see and meet new art expressions. However, it is not good intentions, nor guidelines, that matter, but whether the arts can reflect religious authenticity or significance (Brown 1995: 324-326). The problem for practicing artists is how all these criteria should be understood and integrated in their art producing processes.

In my doctoral thesis, I have argued that the four terms genuine, Christian, modern, and art in principle may be taken to incorporate the desired characteristics of contemporary ecclesial art, provided that genuine points to authenticity understood as spirituality, Christian implies beauty, modern means significance or relevance for the user, and art indicates quality, primarily in the making, figure 1 (Refsum 2000: 175).

.jpg)

Figure 1. Criteria for contemporary ecclesial art (Refsum 2000: 175).

The aspect of genuineness demands according to the US theologian Fr. Mark Boyer, that everything: “must be real in the sense that it is our own” (Boyer 1990: 31). This means that according to contemporary standards, art in the church room should not only pass on tradition, but should be something the congregation can devote to. However, considering the art aspect, quality in art presupposes genuineness in the making and thereby the maker. Therefore, the aspect of genuineness cannot be fulfilled without letting the artist work in accordance with herlhis personal belief or spirituality.

The aspect of being Christian is in the Roman Catholic tradition not related to something in particular or narrations, but rather to beauty. The late Pope John Paul II writes: “Beauty is a key to the mystery and a call to transcendence” (John Paul II 1999: § 16). In Protestant traditions, there may be a stronger expectation towards the narrative, but not necessarily. The title of an artwork, indicating its concept, may also be decisi ve (Achen 1991).

The aspect of modern in ecclesial contexts does not mean contemporary as used in the art world. It indicates that the art in the Church should not be perceived as irrelevant or out-of date to the audience.12 Art in the Church should be meaningful: up to date, relevant or even fashionable.

The aspect of art in this model does not cover the same ideas as in the art world. In the ecclesial context, it is more likely to denote good quality in the making. The US Roman Catholic bishops’ advice in their regulations Environment and Art: “Quality means love and care in the making of something, honesty, genuineness with any materials used, and the artist’s special gift in producing a harmonious whole, a well-crafted work” (Environment and Art: § 20). Concerning furniture and objects in a church is said: “None should be made in such a way that it is far removed from the print of the human hand and human craft” (Ibid. § 67).13

Considering the Context

In addition to the guidelines concerning the artwork, artists who want to work in ecclesial spaces have to consider the context as a whole if they wish to succeed and avoid conflicts:

* the given room: size, style, materials, interior decoration, embellishment and artworks already installed, eventual protection by law etc.

* the users: the congregation, occasional visitors, tourists, maybe officials of state, homeless, refugees etc.

* the local interpretation of Christian ideology: denomination, traditional, moderate or liberal, including the power structures within’ the congregation and the authorities.

The ecclesial task demands handling these components and producing a personally authentic work. Such work may well be defined as design rather than art.

Temporary Embellishment

When speaking about art in ecclesial use, one usually thinks of permanent embellishments. However, the events during the liturgical year are marked by shifts in the colours of the clerical garments, textiles in use and seasonal decorations. 14 Environment and Art says:

Many new or renovated liturgical spaces, therefore, invite temporary decoration for particular celebrations, feasts and seasons. Banners and hangings of various sorts are both popular and appropriate, as long as the nature of these art forms is respected (Environment and Art: § 100).

Temporary decorations may well be artworks. Kunsten a vaere kirke says: “Some of the contemporary art is of a very short duration and therefore may invite an exploration of the use of art in ecclesial spaces that is temporary and flexible” (Kunsten a vaere kirke: 133).15 This opens new possibilities:

One may imagine embellishments that can be projected in the ecclesial space for a restricted period. This diminishes the claims concerning its contents and the material duration of the artwork. One may explore new media that are more fleeting or transient in character, for instance photography, video, installation etc. After some time, the artwork can be removed, while another takes its place (Kunsten a vaere kirke: 133-34).16

A temporary use of art in ecclesial spaces invites more daring art projects. Most congregations will accept untraditional and experimental artworks when they know that they are to be removed shortly. By exposure to new art expressions the understanding of the contemporary may grow and the border of tolerance within the audience gradually may be extended.

Working in ecclesial spaces requires dialogue between all parties involved. If artists wish to go beyond the ecclesial iconographical tradition, they may have to argue for their concepts, not only artistically, but as relevant in the context. The better the arguments, the more likely it is that their ideas will be met positively.

Pater Noster Project

An invitation to intervene artistically in Oslo Cathedral is challenging.17 From the start, it was sternly made clear that the ecclesial context had to be respected, and the Church authorities alone would decide what could be accepted. In the end, only four of the eight invited artists, decided to intervene in the church room itself. 18

The Context

Oslo Cathedral is situated in the heart of the capital. It is an austere brick building, erected in the late 17th century and finished in 1697; today it is protected by law. The cathedral room is large and solemn, filled with interior objects and decorations from the past 300 years, figure 2.

.jpg)

Figure 2. Oslo Cathedral, nave

The Cathedral altarpiece and pulpit are originals from 1699, lavishly decorated with acanthus woodcuts plaited with gold that were typical in Norway in the Baroque period. The altarpiece is an example of the Protestant iconography of its time. Its vertical composition shows the Last Supper at the bottom, the crucifixion in the middle and Christ in glory on top, became a model for later altarpieces, figure 3 (Christie 1973, vol. 1: 56; Brunsvik 2003).

.jpg)

Figure 3. Altar piece carved by a ‘Dutchman’, 1699

Oslo Cathedral is a place of religious ceremonies, celebrations and worship, on a stately national level, as well as for the local congregation, visiting school classes, tourists and homeless. On ordinary days, people come and go, some for liturgy, others to see the room, to pray or meditate, or just to sit silently for a rest. The atmosphere is peaceful.

To be a cathedral means that it is the church of a bishop.19 While the Bishop is in charge, the vicar runs the daily routines. Besides, the congregation has elected a committee that has its say in the administration of the church. Oslo Cathedral has become known for its openness towards all kinds of people. Theologically, the Cathedral has become a centre of inter-religious dialogues with the Muslim citizens in Oslo and Norway.

At the time of the preparations for the art intervention, the former bishop who had balanced wisely between liberal and traditional theological attitudes, retired and was replaced by a bishop who is more traditional in his opinions?20 Under such circumstances unnecessary provoking incidents, for instance from temporary art interventions, had to be avoided. Still, the vicar wished to continue the open-minded attitude towards contemporary art and the willingness to let the visitors of the cathedral enjoy new art in the old building.

Towards an Artistic Idea

When I began my work in the Cathedral, I had no idea of were to start or what to make. Entering the Cathedral, I wondered if anything could successfully be added in this delicately balanced room that seemed filled with inherited artefacts and decorations from various periods of the past 300 years. The old altarpiece is powerful, visually telling the basic Christian story. Was there more to say, and if so, what could it possibly be?

My working method when I am at a loss of what to do is· to let everything go and start meditating. Sitting quietly in the Cathedral nave, being and watching, I became aware of the huge space between the bench tops and the ceiling and the empty volume between the altar piece and my sitting position. I decided that this might be the site to intervene.

I asked myself: what is the essence within this room, what happens here and how can it be commented upon? The room is one of liturgy, which is shared, communal prayer. I wished to work on prayer or meditation, but the question was how it could be related to the liturgy.

The altarpiece is the viewpoint for visual mediation. It is catechetical and decorative, the figures are familiar representations of the Christian narrative, challenging 300 years ago, but what about today, what may be its equivalent now? Could I go into a dialogue with its fundamental motives? I envisioned a transparent hanging in front of the altarpiece that might constitute a new, contemporary layer of Christian interpretation and meaning, which was related to the daily liturgy. Thereby a genuine new dimension could be added to the old story told visually in the altarpiece. Since there is an installation for lightning in front of the choir, it was technically possible. Before moving on with the idea, I contacted the vicar and asked his opinion. In principle he was positive, but the acceptance would depend on what I made.

Text and Ornament

I had decided a site for intervention and to work on prayer as the general theme. Furthermore, I wished to build on the Protestant tradition as such, transcending the I ih century Cathedral building and its interior. The challenge was to decide how.

The Reformation in 1537 marks the split between the Western Roman Catholic Church and the new Protestant Churches. The question of the right theological interpretation and the use of images were central in this conflict. The new Protestant Churches accentuated preaching; images, embellishments and arts, but for music, were merely pedagogical tools (Bugge 1975: 196). During the 16th century in Norway much of the old interiors were kept. The few new embellishments that were made in this period are marked with the pedagogical focus of the time, combining imagery and instructing texts (Bugge 1990). The altarpiece from Seljord Church from 1588, is an example that is very well known. It shows the 10 Commandments, including the Mosaic ban on pictures that were important for the Protestants, figure 4 (Christie 1975: 211; Christie 1982: vol. 3: 143).21

.jpg)

Figure 4. Altarpiece from Seljord Church, Telemark, Norway, 1588 (postcard)

The altarpiece in Oslo Cathedral initiated a new era within Protestant iconography (Christie 1973, vol. 1: 20). It must have been highly modern – may be daring of its time without any instructing texts – with its figurative visualization and rich ornaments, both pleasing to the eye. However, I always felt an attraction towards the early lettered Protestant altarpieces, the beauty of the old handwriting and the idea of combining image and text, or turning text into image, figure 5. Formally, and may be conceptually, they may be considered close to today’s art using texts, words and lettering (Morley 2003).

.jpg)

Figure 5. Wing from an altarpiece ca. 1590, Ballerup Church, Denmark. Lord’s Prayer written in Latin and Danish (Nationalmuseet, Copenhagen).

The Cathedral milieu in Oslo is leading in ecumenical and inter-religious work in Norway. For Jews and Muslims depiction of the sacred and God are out of the question, their religious embellishing traditions are ornamental and geometric. The early Protestants are close to this understanding in their attitude to images. To contribute to an increased understanding between Christianity and other religions, I build upon that which is shared, showing similarity between the traditions rather than differences. Since the altar piece is figurative and exclusively Christian in form, I decided to contrast it by being iconoclastic,22 and highlight the ornamental tradition within Christianity: I decided to write a prayer.

Lord’s Prayer

Lord’s Prayer is considered the model prayer for all Christian denominations. When the disciples, according to Scripture, asked Jesus how to pray, he taught them this prayer named after its first two words: Our Father in English, Pater Noster in Latin.23 Our Father became a liturgical prayer of the Christian community in the first century. It was used in the baptismal liturgy and before the Eucharist in the early Church.24 Today, it is said before Communion in the Eucharist.25 If anything unites Christians universally it must be Lord’s Prayer. Therefore, I chose Lord’s Prayer as the prayer to write.

I envisioned a transparent hanging of Lord’s Prayer set in the space between me sitting on a bench in the nave, and the 300 years old images of the altarpiece. To materialize the invisible, said prayer into the open space in front of the altarpiece would create a double layer of Christian interpretations that the praying congregation could look at: one figurative from 1699, the other textual from 2005. This intervention would suggest a praying or contemplative attitude towards the biblical events depicted on the altarpiece, and a reflecting and interpretative or hermeneutic attitude to the Christian narrative.

A hermeneutic approach to biblical texts belongs to the tradition of the Church?26 During the 20th century, however, the new knowledge gained through historical critical theological research has caused the raise of a contemporary fundamentalist reaction within Christianity.27 Lord’s Prayer is ecumenically shared and under no circumstances controversial in itself. What causes trouble, however, are the translations?28 In accordance with the Lutheran spirit of going back to the sources, I decided not to write one of the newest versions, but rather an old. To underscore that everything related to Christianity has to be interpreted, I chose to write in Latin that is the theological language of the Western Church, and the language of the time the Cathedral was built. By writing the Latin prayer today, the intention was to go into a dialogue with the altarpiece that went behind its “modem” 1699 expression, leading back to 1st century. I wished to show that being in church praying is to be exposed to the 2000 years long tradition in which the prayer we say today is only one version along with all the others. Instead of provoking by personally interpreting Lord’s Prayer, I chose to step back to the traditional version. This version would seem old to the congregation and indicate the museum like character of the altarpiece. Thereby, I wished to create a mental space for individual interpretation, now.

To underscore the traditional version of Lord’s Prayer, I let the physical composition build on well known iconography. Many postcards circulate with Our Father written in several languages framed with floral patterns?’) This composition is elaborated in 140 images of ceramic tiles on the atrium walls in the Convent of Pater Noster in Jerusalem, built in 1870 near the site where Jesus is considered to have taught his disciples to pray. This iconography became point of departure for composing the work; besides, a floral framing would dialogue with the acanthus leaves of the altarpiece.

Material and Technique

I work with metal thread that I bind by hand, in accordance with the advice of Environment and Art (§ 67), as the constructive element in my art-/design work. This time, I decided upon galvanized, iron thread that is shining grey as new, and becomes dull grey turning towards the blue during time. This would be my “ink” for writing. Wasted glass in shades of green was added as the vegetal component that might respond to the altarpiece acanthus and accompany the text. I intended to use the green with sensitivity and care, avoiding interference with the colourful stained glass paintings in the choir.

My hand binding technique limits the size in which to work. But crafting is an essential mean to express the meditative aspect. Especially in the Cathedral space, I wished to keep contact with my bodily dimensions. However, I was afraid that my work would turn out like a small fragile stamp, hardly visible in the void. So be it! 1 decided that such an outcome might well be an appropriate expression of my feelings and position in the room.

As a start, I planned the final work to be ca. 1.7 x 3.5 m, allowing for an ornamented frame and some variation in length, due to the actual writing of the given text. Otherwise, the construction should be as light as possible, but strong enough to hang straight.

The Lord’s Prayer consists of 10 separate prayers that I set on lines and counted the letters and the spaces in between. I could not foresee the composition as a whole.

Pater noster Qui es in crelis (28)

Sanctificetur nomen tuum (24)

Adveniat regnum tuum (20)

Fiat voluntas tua sicut in crelo (32)

et in terra Panem nostrum (20)

cotidianum da nobis hodie (25)

Et dimitte nobis debita nostra Sicut (36)

et nos dimittimus debitoribus nostris (37)

Et ne nos inducas in tentationem (32)

Sed libera nos a malo Amen (26)

The letters had to be connected to give the object constructive strength. I chose horizontal lines of two twisted threads (0.9 mm), figure 6.

.jpg)

Figure 6. Horizontal lines

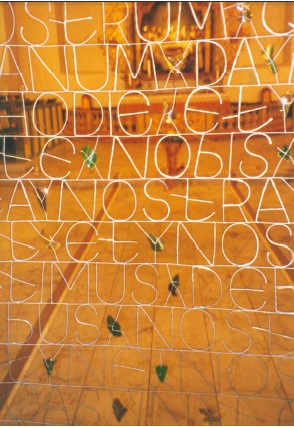

.jpg)

Figure 7. Lettering

For the letters I chose a fairly thick, single thread (1.65 mm) that would bind the lines together vertically and would be possible to bind onto the lines figure 7. This is a balance that demands experiential knowledge. The thread was hammered (smithed) to gain strength. The letters were mostly connected to the horizontal lines by a third, soft thread (0.9 mm), or the thick thread was bound directly to the wire, figure 8. The solution with the third thread is not particularly strong, but practical because the letters can easily be moved without craclcing. Bound threads cannot be unbound more than a couple of times before they break.

Each letter was formed individually and hammered, due to position and connecting possibilities. The aim was to make an ornamental, meditative image, more than to write an instructional text. Bits of glass were set between the words for decorative purpose and to heighten the readability. The glass cuts have random forms generated from smashed bottles, figure 8.

.jpg)

Figure 8. Glass cuts between words

.jpg)

Figure 9. Overall composition

The positioning of letters and glass creates the overall impression, density and transparency of the image. The composition was regulated in accordance with the principles of stained glass painting, in which the picture plane shall be kept flat, allowing the eye to wander freely around without stopping. The skilled performance creates a surface that perceptually has no holes, figure 9.

The initial idea of making a floral frame of pieces of glass around the construction proved to be wrong. The text in all its irregularity became so rich that such a frame would compete with it. After some experimenting, I had to give up the idea of a fancy frame. This was frightening as the composition now diminished dramatically, and the worry of the tiny stamp in the huge space, instantly popped up. However, the frame had to be minimal. It was made by twisting two thick threads (1.65 mm) into a wire that got sufficient strength to carry the weight of the text, still it was fairly soft. To strengthen the construction, top and bottom got a double border with a simple row of glass cuts in between that came to represent the intended floral frame, figure 10.

.jpg)

Figure 10. Top border

The work shrank to 126 x 257 cm. It was installed as planned and to my astonishment the hanging filled the given space. The contemporary written Pater Noster managed to balance the monumental Baroque altarpiece. The grey thread that I feared would become invisible became slightly blue in contrast to the complementary gold in the interior. Interestingly, the green glass that I thought would create a lively connection to the organic acanthus, made the latter seem old and withered. It gave an unpredicted tension between the old and the new that to me was an unexpected bonus.

The Pater Noster hanging was part of an exhibition and it was clear to everyone that this was a temporary embellishment, figure 11 a-b.

.jpg) |

|

Figure 11 a-b. Pater Noster hanging in Oslo Cathedral (126 x 257 cm) October 2005

By taking part as lector (the reader of the texts) in Sunday mass prior to the exhibition opening, a link was established between the congregation and the makers of the artworks for display. Acceptance for the new was gained by respecting the worshippers.

Conclusions

What should the artist consider when doing ecclesial work? Firstly, shelhe has to reflect on what kind of project it is, permanent or temporary, its purpose and goal. Secondly, shelhe has to decide her/his role within it. Thirdly, the context must be understood: the given room, the users and the local interpretation of Christian ideology. Fourthly, the concepts genuine-Christian-modern-art may represent a useful checklist for the work to be produced.

In the Pater Noster project, I chose to work from within the Christian tradition, taking a loyal, critical attitude. This may be considered unacceptable from a contemporary art perspective (l00 Artists See God 2004). However, my intention was to work in accordance with the principles of ecclesial art, which from a contemporary art viewpoint may well position the work as catechetical design. Evaluating the Pater Noster project in relation to the ecclesial genuine-Christian-modern-art concepts, I will argue that: it is genuine, representing a personal interpretation of tradition that reveals a spirituality connected to silent prayer and meditation that goes beyond present times. Its concept is Christian by choice of theme and attitude, but also Protestant in its catechetical and puritan attitude, formally and conceptually. The formal solutions: site of intervention, minimalist expression, ornamentality, hand-crafted making, and every-day cheap material and scrap used, combine tradition and the contemporary in a new multilayered vision that invites further interpretation. It is not for the artist to judge whether the outcome of her/his working process is successful: an artwork of quality, with a beauty that communicates the old Christian narrative relevantly to a modern audience. However, the reception was overwhelming from the Cathedral authorities.

I consider the present paper an example of artistic research. It is a retrospective reflection, an analysis of an art/design development work accompanied by compiled understanding from previous research work, including my own, that sheds light on the art/design project. The art/design work itself was started and carried out as professional practice, that is, done more or less intuitively and spontaneously, but all the same built on my knowledge of the subject. Being trained in documenting my work, I took photos during the process. As I see it, research is connected to the task of reflection and systematization in order to create new understanding of anything. In the case of the art/design practitioner, this anything may well be her/his personal art/design work.

Traditional research processes are initiated by a question of what, and a proposal of the answer. However, this very paper demonstrates how I as a practicing artist/designer find it beneficial and useful to work. It helps me become aware of what I have done and sets my work in a wider context. It inspires me to go on learning more. Through articulation, I create transparency in my working process and can take part in a broader discourse; it invites response and criticism of my thinking and the choices taken. ArtIdesign is personal, so is an art/design development work, but artists/designers are embedded in a tradition they extend. Whatever the artist/designer say about her/his work has relevance for other artists/designers dealing within the same field. What the individual artist/designer understands thus becomes part of the articulated knowledge of the field (Refsum 2007).

*******

Notes

1 Ecclesial means “churchly”. It is explained further in the first part of the paper Terminology.

2 Abbreviated Kunsten a vaere kirke. In English: The Art of Being Church; Church, Art and Culture. All translations between English and Norwegian are done freely by the author.

3 Begge freistar a skape eit rom for reneksjon over kva det vii seie a vere menneske [ … ] uansett utgangspunkt, kristen eller ikkje, handlar det om a leite seg fram til møtestader der vi kan vere med pa a utforme skissene til ei meining som rna rekonstruerast igjen og igjen (Kunsten a vaere kirke: 11 and 9).

4 Ibid.: 10. The contemporary philosophers Gianni Vattimo and JUrgen Habermas are exponents for this stance (Vattimo 1999; Lysaker and Aakvaag 2007).

5 Ibid.: 20 I. Kirken rna gjenerobre noe av sin tapte fortid som padriver for fomyelse. Den rna aktivt bryte med den forsiktigheten som har preget kirkens møte med kunsten i mange generasjoner. I stedet for a innta en konservativ, kontrollerende og skeptisk grunnholdning til samtidskunst, rna den bli en bidragsyter til a utvikle kunstuttrykket. Skal kirken ha et sant nrervrer i samliden og kjenne og forsta menneskenes hjerter, er det viktig at den legger til rette for at dagens stemmer kan bli hørt.

6 The terms Christian, ritual and church art may occur, but have slighlly different meanings (Refsum 2000: 40-48).

7 Theologically, there are distinct differences between the consecration or dedication of Roman Catholic and Protestant church buildings. In Roman Catholic church rooms the holy is present by relics and the Eucharistic sacrament, which is kept there, while in Protestant churches the holy in principle is constituted through the presence of people. The consequences of this difference and the status of the various church rooms are not clear. As an artist, I leave the further discussion of this question to theologians.

8 In Norwegian: “en gjenstand er sakral nar den i funksjon, materiale og formsprak sikter pa a tjene Guds folk i dets felles, liturgiske liv”.

9 Etymologically, liturgy sterns from Greek leitourgia, which is a combination of leitós, an adjective meaning pertaining to the people, and érgon, work (New Catholic Encyclopedia 2003, vol. 8: 727).

10 I define my artwork as ecclesial art regardless of where it is kept, because I conceptually relate it to Ecclesia.

I1 Presentation at Nordisk Kirkesagskonference, organized by Kirkefondet, Arhus 6-9 August 1996.

12 This explains how icons that belong to the Orthodox tradition founded on the style of 6th century on have been considered modern in Western Churches during the latest decades.

13 I refer to Environment and Art not to promote Roman Catholic teachings as such, but rather because this work is currently the most elaborated text on this topic.

14 The liturgical year is marked with different colours: violet, white, red and green. Well-known seasons with popular decorations are: Advent (wreath), Christmas (crib and tree) and Easter (tree with eggs). Additionally, there are feasts, ecclesial duties and sacraments: baptism, confirmation, wedding and funeral that may have separate decorations.

15 “Samtidskunstens til dels svrert korte varighet kan tale for at man i store grad burde utforske bruk av kunst i kirkerommet som er mer fleksibel og utskiftbar”.

16 “Man kan tenke seg utsmykninger som projiseres i kirkerommet for en begrenset periode. Dette minsker kravene til kunstverket om bade uttrykksmessig og materiell varighet. Man kan utforske nye medier som er av en mer flyktig eller ubestandig karakter, for eksempel fotografi, video, installasjoner etc. Etter en stund kan kunstverket fjernes eller flyttes til andre deler av kirken, mens et nytt verk far plass”.

17 I had previously shown a cross sculpture during a liturgical celebration, but otherwise exhibited in the crypt.

18 Helen Eriksen, Rosalind Murray, Paula Chambers and myself worked in the cathedral room, the others preferred the crypt. In this paper I solely speak about my personal work since each of us worked separately with their own topics and places in the room.

I9 Cathedral from Latin cathedra, the seat of the church authority (The New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, vol. I: 353).

20 Particularly the question of ordaining homosexual priests is an unsettled issue.

21 The Second Commandment forbids making images of God, Yahweh (in this altarpiece it is included in the first) In Exodus 20:2 is said: “You shall not make yourself a carved image or any likeness of anything in heaven or on earth beneath or in the waters under the earth” (The Jerusalem Bible 1966, GT: 102).

22 From Latin iconoclastes, original from Greek eikonoclastes, a destroyer or opponent of religious images, icons. The term came into use in the 8th century during the debate on image veneration, and returned in the 161 century ruritan period of early Protestantism (The New Shorter Oxford EngLish Dictionary. vol. I: 1302).

23 This prayer is found in two versions in the Gospels: Matthew, 6:9b-13, and Luke 11:2b-14.

24 New Catholic Encyclopedia 2003 vol. 8: 784.

25 See online: http://www.kirken.no/?event=doLink&nodeID=23919.

26 St. Augustine (354-430) is considered the father of hermeneutics (see online: http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/02084a.htm.

27 Fundamentalism regards the Bible as the word of God that should not be interpreted according to its context.

28 In Norway, recurrent controversies catch fire every time renewals are introduced. The Roman Catholic Church in Norway that reestablished herself in the mid 18th century, has solved the problem by refusing renewals, and keeps to the old text.

References

100 Artists See God. 2004. Edited by J. Baldessari and M. Cranston. Catalogue. Travelling Exhibition organised by Independent Curators International (ICI), New York. Curated by John BaLdessari and Meg Cranston. London: Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA).

Environment & Art in Catholic Worship. 1993. Edited by National Conference of Catholic Bishops Bishops’ Committee on the Liturgy. Chicago: Archdiocese of Chicago. Original edition, 1978.

Kunsten a vaere kirke; am kirke, kunst og kultur. 2005. Edited by Norske and kirkeakademier, Kulturmelding for Den norske kirke. Oslo: Verbum.

New Catholic Encyclopedia. 2003. 2 ed. Detroit, New York etc.: Thomson Gale, in association with The Catholic University of America, Washington, D. C. Original edition, 1967.

The Jerusalem Bible. 1966. Standard Edition. London: Darton, Longman & Todd.

The New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary on Historical Principles. 1993. Edited by L. Brown. 2 vols. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Original edition, 1933.

Achen, Henrik von. 1991. Das Problem des Titels in der modernen christlichen Kunst. Das Münster Jahrg. 44 (Heft 2): 103-106.

Brown, Frank Burch. 1995. Christian Theology’s Dialogue with Culture. In Companion Encyclopedia of Theology, edited by P. a. H. Byrne, Leslie. London, New York: Routledge.

Brunsvik, Hilde. 2003. En guide til Oslo domkirke. Oslo: Oslo domkirke.

Bugge, Ragne. 1990. Tekstaltertavlene i Danmark-Norge omkring 1600. In Reformationens konsolidering ide nordiska liinderna 1540-1610, edited by 1. Brohed: Universitetsforlaget.

Bugge, Ragne. 1975. Holdninger til bilder i kirkene i Norge i Reformasjonsarhundret. In Fra Sankt Olav til Martin Luther. Foredragfremlagt ved det tredje nordiske symposionfor ikonografiske studier, Bardshaug 21.-14. August 1972, edited by M. Blindheim. Oslo: Universitetets Oldsaksamling.

Christie, Sigrid. 1982. Maleri og skulptur 1536-1814. In Norges kunsthistorie, vol 3, edited by J. H. Lexow, S. Christie, A. Polak and P. Anker. Oslo: Gyldendal norsk forlag.

Christie, Sigrid. 1975. Tema og program i den gammellutherske ikonografi. In Fra Sankt Olav til Martin Luther. Foredrag fremlagt ved det tredje nordiske symposionfor ikonografiske studier, Bardshaug 21.-14. August 1972, edited by M. Blindheim. Oslo: Universitetets Oldsaksamling.

Christie, Sigrid. 1973. Den Lutherske ikonografi i Norge inntil 1800. Vol. I and II. Oslo:

Riksantikvaren. Land og Kirke.

Frehn, Helge. 1968. Gudstjenestens rom – pa en annen mate. In Kirkens arv – kirkens fremtid. Festskrift til Biskop Johannes Smemo pa 70-arsdagen 31. juli 1968. Oslo: Forlaget land og kirke.

John Paul II, Pope. 1999. To Artists [Letter]. Vatican [cited 23.012007]. Available from https://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/letters/1999/documents/hf_jp-ii_let_23041999_artists.html

Jungmann, Josef. 1955. Church Art. Worship XXIX (II):69-82.

Lysaker, Odin, and Gunnar C. Aakvaag. 2007. Habermas, kritiske lesninger. Oslo: Pax.

Morley, Simon. 2003. Writing on the Wall. Word and Image in Modern Art. London: Thames and Hudson.

Rahner, Karl, SJ., and Herbert Vorgrimler, eds. 1983. Concise Theological Dictionary. London:

Bums & Oats.

Refsum, Grete. 2007. Personal Theory; Towards a Model of Knowledge Development for Design. Paper read at NORDES, Nordic Design Research Conference, 27-30 May, at Konstfack, Stockholm.

Refsum, Grete. 2000. Genuine Christian Modern Art. Present Roman Catholic Directives on Visual Art Seen from an Artist’s Perspective. Dr. ing., Oslo School of Architecture, Oslo.

Vattimo, Gianni. 1999. Belief. Cambridge: Polity Press. Original edition, 1996.

Grete Refsum has a broad academic and artistic background; 1977, MA Environmental Manager, University of Agriculture; 1978, Examen Philosophicum, University of Oslo; 1985, Diploma, Painting/stained glass; 1992 MA, Form, National College of Art and Design; 2000, Dr. ing., Oslo School of Architecture. Refsum is currently part time (50 %) employed in Oslo National Academy of the Arts as Senior Adviser of research and development and as Adjunct Professor. Refsum has during 20 years contributed to the development of research in art and design through her artistic development work and practice-led research, publishing and taking part in the international discourse on these issues through many conferences and publications. Artistically, Refsum has systematically explored the Western Christian heritage and tradition, interpreting central themes like: the cross/crucifix, sacraments, prayer and liturgy. For the last 10 years, she has focused on prayer/meditation. Refsum is a pioneer of using art experimentally in catechesis and ecclesial spaces. Her practice comprises: embellishments, art interventions, performances, workshops and shows of various kinds. Several of her art works are regularly being used liturgically. www.refsum.no